I am not sure when I flew on an airplane for the first time, but it might have been when I went from Seattle, where I was born and raised, to San Francisco, California, to check out the University of Santa Clara as a possible site for my ongoing educational endeavors. Since then, I have taken many flights, long and short, on a variety of airlines. During my interminable wait for the initiation of my most recent journey I tried to remember them: Delta, United, Alaskan Airlines, Pan Am, Jet Blue, Singapore Airlines, Thai Airlines, Icelandic Airlines, Turkish Airlines, Indian Airlines, Aegean Airlines, Olympic Airlines… There must have been others. The longest direct flight I ever took was from San Francisco to Hong Kong; that one lasted seventeen hours. The shortest? I’m not sure. It might have been from Athens to Thessaloniki in Greece; there was hardly time for the plane to gain altitude before it started to descend. Or maybe it was the stretch from Jakarta, Indonesia, to Singapore. Regardless of which airlines I have flown on, though, or the distance of the journey, I have almost always, out of necessity, flown economy class.

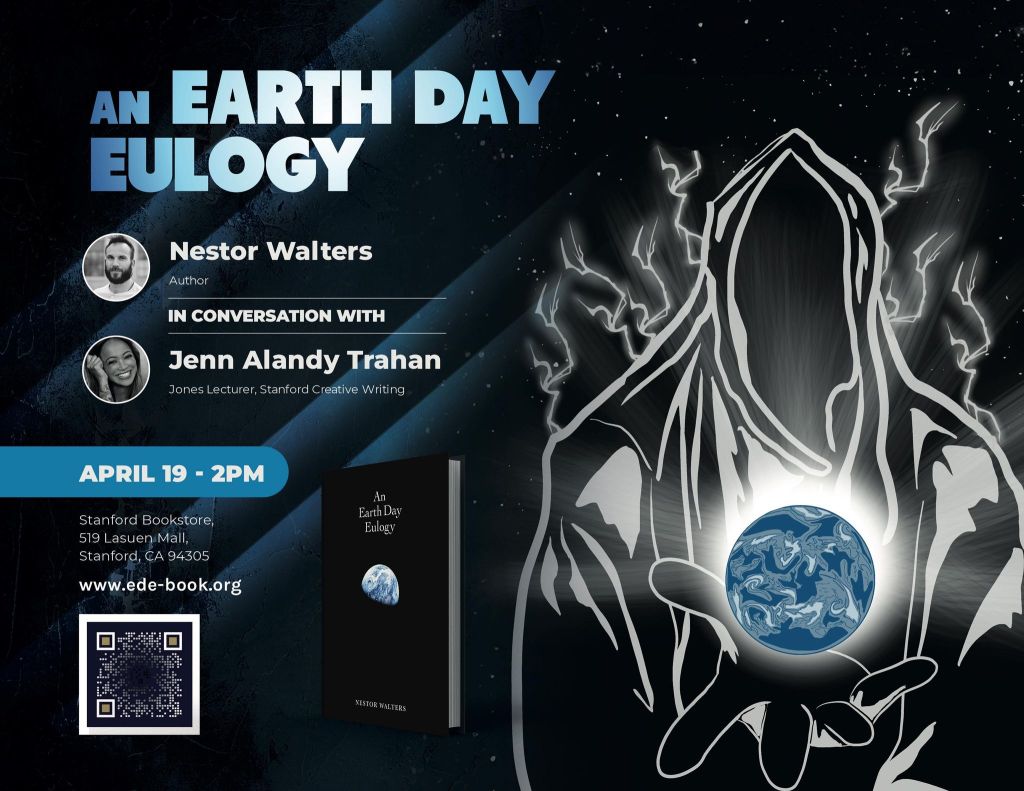

And so we come to my latest aviation adventure: flying from Seattle to San Francisco aboard Delta Airlines so I could attend the book launch of the first novel written by one of my sons. I have always enjoyed flying on Delta in the past; indeed, I considered it one of my preferred airlines. I think that the trends I observed on this flight are ubiquitous across all airline companies. They are all struggling. They are all trying to save money. Their penuriousness, though, has become an obsession to the point where they ignore or denigrate the people that it’s all for: the passengers.

As I mentioned, I have almost always flown economy class, in contrast to first class, but this difference has invariably been relegated in my mind to the realm of who gives a damn anyway? There was a time that even in economy class a person could enjoy a modicum of comfort. Those times are long gone. I’m not just talking about leg room here; I’m talking about degradation and humiliation. On this flight there was not just first class and economy, no; there were six levels of seating. First class was primary, of course, and then came comfort plus, followed by three more levels whose names I forget, and finally, beneath the rest and last to board, was my level: economy basic. The “basic” is the verbal equivalent of a sneer, as if it carries a stigma, as in “don’t ask; you’re entitled to nothing.”

People in economy class have no rights – not even the right, as I have always had in times past, of seat selection. As soon as I got my reservation, I went to the Delta website so I could choose a seat, only to be informed that I couldn’t get a seat assignment until I checked in – because of my class. If I wanted to grab a specific seat before then, I had to pay a fee of thirty-five dollars. I cannot remember this happening before on Delta or any other airlines. I dutifully waited until twenty-four hours before the flight to check in online, and then went for my seat, only to be met with the same prospect of a thirty-five dollar fee and a notice that I had to be assigned my seat at the gate. Okay, then, damn it. I really wanted an aisle seat so the sardine-like stuffed-in feeling would be somewhat mitigated, so I got to the gate over two hours early; there I was told that economy basic passengers could only obtain seat numbers one hour before the flight. None of this is communicated in advance; I had to pass through numerous trick doorways to find it out.

They’d also way overbooked the flight, by the way, to the extent that they had to offer passengers gift cards if they would agree to take a later flight. They started by announcing four hundred dollar offers and raised these all the way to one thousand dollars before enough people volunteered to defer their trips until later. To top it off, the flight was delayed for over an hour due to ongoing construction in San Francisco. It made me wonder: if they knew about the construction, why could they not better plan for it?

And then there was the carry-on situation. At first, the gate attendant announced that overhead bin space was limited and requested passengers to voluntarily check their carry-on bags at no extra charge. However, when I boarded – as an economy basic passenger one of the last, of course – as I passed the attendant she snatched my bag out of my hands and said, “We’re checking this,” and before I could protest and explain that it could easily fit under the seat in front, she’d slapped a tag on it and set it aside. I had no option but to comply, even though it had things in it I’d intended to use during the flight – my Kindle Fire, for instance – but then, they were charging extra for the wifi too, so I probably wouldn’t have utilized it.

I had an aisle seat in the very back row of the plane, which didn’t bother me much because it gave me an opportunity to chat with the stewardess. I found out she was scheduled on four flights that day: Portland to Seattle, Seattle to San Francisco, San Francisco to Seattle, and Seattle to Portland. A brutal schedule, to be sure! And she had a similar schedule the next day. She seemed chipper enough, though, in spite of it. Ah, to be young again!

No meals were served on the flight, not even to those in first class. Instead, the stewardess moved down the aisle dispensing coffee, tea, soft drinks, potato chips, almonds, and similar items from a snack cart. You could request alcoholic beverages – for a steep fee. I remember a time when, even on these relatively short flights, complementary hot meals were served to all classes of passenger. Beer and wine were free on most flights too. On one of my longer trips, from Auckland, New Zealand, to Los Angeles – in economy class, mind you – I called the stewardess to request a wine refill a few times, and fed up, she finally brought a half-full bottle to me and said, “Here, just keep this.” Those were the days!

Finally, let’s close on a positive note, with an airline improvement. Yes, a few things at least have got better over the years. When I went to the bathroom, I noticed an ashtray, although there was also a no smoking sign. It caused me to remember the days when smoking was allowed on flights, and aircraft had smoking and non-smoking sections. That’s a thing of the past I definitely don’t miss. Can you imagine how dense the air was and how much it stank in the sealed-in container of the airplane? But that’s how it was back then. You could smoke almost anywhere: restaurants, offices, planes, trains, and so on. Just about anywhere except, of course, in church.